What is a public option, and why are we concerned about it?

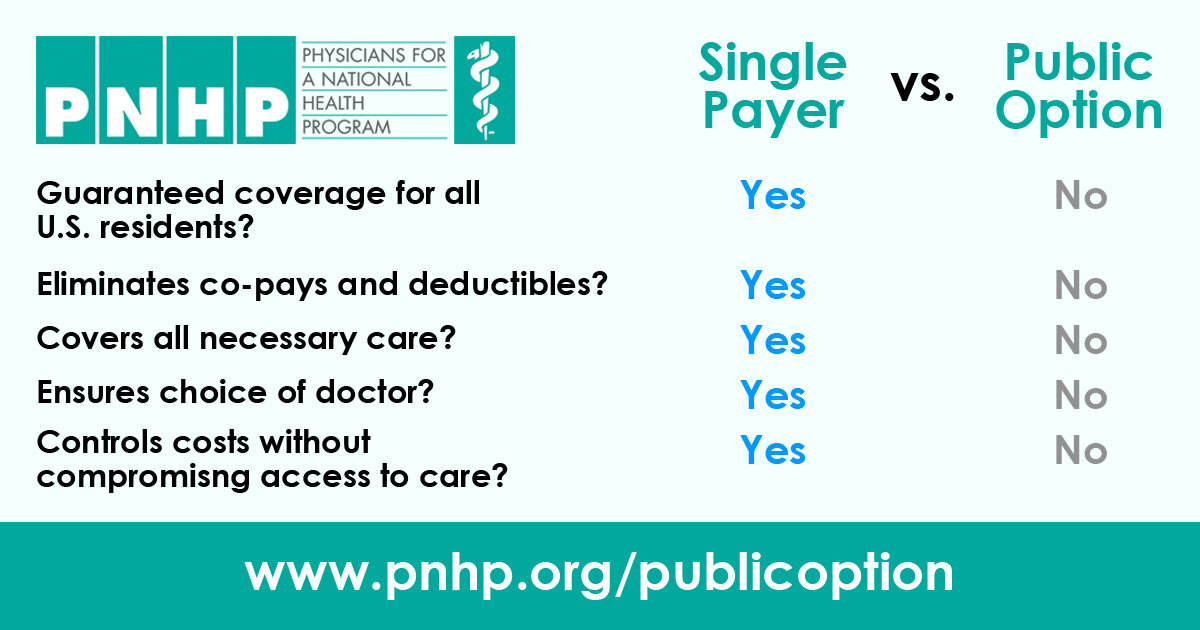

A public option is a publicly run health insurance plan that would compete with private health insurance companies. The Chart below compares public option schemes with single payer/improved Medicare for All.

A Medicaid buy-in in Oregon: This is sometimes thought of as an example of a public option. It has all of the potential problems of a public option, but it has even more problems, since we expect that it will be proposed as buying in to privately controlled Coordinated Care Organizations (CCOs). While the state has more control over CCOs than it has over other private insurers, CCOs still use public money to successfully lobby for non-transparency related to their most important use of the dollars we earmark for healthcare of low-income Oregonians - reimbursing providers for care. CCOs still expand the problems caused by splitting the risk pool and require risk adjustment, unless the state changes the method by which it pays CCOs, which it probably cannot do during the period of contracts which run through 2024. Risk adjustment is necessarily administratively complex and necessarily enhances inequities relative to a single payer system.

Why a Public Option Will Probably Not Help Move Us to Single Payer

A public option is very unlikely to help our efforts to get improved Medicare for All at the federal level or a decent single payer system at the state level. One of the best explanations of why can be found in an October 2019 article by David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler – The ‘Public Option’ on Health Care Is a Poison Pill.

Why do we worry that a public option not a step towards improved Medicare for All?

Private insurers will compete skillfully to appeal to those who don’t expect to need much care, while the public option must accept all applicants. This is adverse selection. The public option will subsidize the private insurers, as they exclude costlier patients by limiting benefits. Private insurance premiums will go down while public option premiums rise, or taxpayer subsidies increase.

The structurally inevitable increase in public option premiums and/or taxpayer subsidies will bolster myths that government run insurance is costly and inefficient. Reinforcing anti-government myths will impede transition to improved Medicare for All.

Existing evidence shows our worries are well-founded. As the article from The Nation states:

No working models of the buy-in or pay-or-play public option variants currently exist in the United States, or elsewhere. But decades of experience with Medicare Advantage offer lessons about … how private insurers capture profits for themselves and push losses onto their public rival – strategies that allow them to win the competition while driving up everyone’s costs.

Does the direct usefulness of a public option justify it if it does not help us get to improved Medicare for All?

A public option maintains the complex administrative costs of fragmented health care. Estimates of this waste, in excess billing, claims denial, and insurance-related activities in provider offices, is as much as $500 billion annually – see, for example, Single-Payer Reform: The Only Way to Fulfill the President's Pledge of More Coverage, Better Benefits, and Lower Costs

A public option will not reduce treatment of healthcare as a discretionary market commodity, which is the main reason the system is so inequitable and unaffordable.

A public option will not curb the unsustainable growth in the fraction of our GDP that goes towards health care.

Can a Medicaid buy-in in Oregon be a useful interim step? Without a more specific and detailed proposal, we cannot make a rational judgement. Some notions to consider when a detailed proposal exists -

Is the buy-in premium affordable for individuals or families?

Is the buy-in to a particular CCO, or can one buy-in to the Oregon Health Plan (OHP) open card?

Will the number of people buying in increase the demand on providers who are getting low reimbursement rates for services sufficiently to decrease care for those currently getting services financed by the OHP?

Is the buy-in price sustainable? If it is attractive enough, it will tend to encourage those who need care to buy-in, and it will then likely require increased public subsidies or an increased price to continue.

Will the proposed buy-in come with improvements in CCO transparency, governance, and structure (e.g. - requiring CCOs that can be bought into to be non-profits, requiring them to transparently share reimbursement rates to providers, requiring them to transparently report and/or seriously restricting lobbying expenses)?

Insurance companies have already shown a willingness to fight tooth and nail against a public option – recall their efforts against including a public option in the Affordable Care Act. If we are going to fight hard enough to win against the corporate healthcare complex, we should be fighting for what we know will be a much more equitable and affordable system – single payer/improved Medicare for All.

Below is a more detailed chart from PNHP -

In EVEN more detail, for those interested

Administrative complexity –

Most of excess administrative costs in the U.S. healthcare system are in provider offices. Excess costs also exist within insurance companies, which pay a smaller share of their revenue to provide patient benefits than does an efficient program such as traditional Medicare. Patients and employers are also burdened by spending substantially more time dealing with healthcare financing decisions than in other countries, or than we would with improved Medicare for All. A public option will not do anything to reduce most of this administrative burden.

The Gee and Spiro article below estimates the excess administrative costs at $248 billion in 2019 based on a Center for American Progress study, at $340 billion based on work by Alexis Pozen and David M. Cutler, and at $504 billion based on work by Woolhandler and Himmelstein comparing U.S. administrative expenditures with Canada. While there is uncertainty as to how much administrative waste there is, even the low estimates suggest substantial savings can be achieved if we can learn from other countries.

Henry Broeska, a Canadian medical researcher now living in the U.S. who has worked in both systems, has produced a graphic comparing the U.S. claims adjudication process with the Canadian process. It becomes clear why the U.S. system spends so much more on administration. A public option will not help this at all, since it does not decrease the number of payers nor change the rules that corporate insurers must follow.

Himmelstein et al. provide data that shows that single payer systems paying hospitals with a global budget have hospitals that average 12% of total costs on administration, while U.S. hospitals spend over 25%. With hospital expenditures constituting 30% of total health care expenditures, administrative savings in hospitals alone could amount to $140 billion annually. A public option will not make global budgets for hospitals any easier – it is exceedingly complex to design a system that pays hospitals with global budgets when there are multiple payers.

References for Administrative Complexity

Austin Frakt, The Astonishingly High Administrative Costs of U.S. Health Care, July 16, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/16/upshot/costs-health-care-us.html

Emily Gee and Topher Spiro, Excess Administrative Costs Burden the U.S. Health Care System, April 8, 2019. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/healthcare/reports/2019/04/08/468302/excess-administrative-costs-burden-u-s-health-care-system/

Henry Broeska, Healthcare Claims Processing, Oct 1, 2019. https://www.healthcare4allhandbook.com/my-blog/healthcare-claims-adjudication

David U. Himmelstein, Miraya Jun, Reinhard Busse, Karine Chevreul, Alexander Geissler, Patrick Jeurissen, Sarah Thomson, Marie-Amelie Vinet, and Steffie Woolhandler, A Comparison Of Hospital Administrative Costs In Eight Nations: US Costs Exceed All Others By Far, September 2014. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1327

Corporate insurance schemes to increase profit will lead to adverse selection

Insurance companies have decades of experience in making money with their insurance plans. In order to make substantial money, they must pay out less in healthcare expenditures than they collect in premiums. The legal ways that they do this generally fall into four types of schemes (quotes below are from Himmelstein & Woolhandler article):

“Obstructing expensive care. Plans try to attract profitable, low-needs enrollees by assuring convenient and affordable access to routine care for minor problems. Simultaneously, they erect barriers to expensive services that threaten profits—for example, prior authorization requirements, high co-payments, narrow networks, and drug formulary restrictions that penalize the unprofitably ill. While the fully public Medicare program contracts with any willing provider, many private insurers exclude (for example) cystic fibrosis specialists, and few Medicare Advantage plans cover care at cancer centers like Memorial Sloan Kettering. Moreover, private insurers’ drug formularies often put all of the drugs—even cheap generics—needed by those with diabetes, schizophrenia, or HIV in a high co-payment tier.”

“Cherry-picking and lemon-dropping, or selectively enrolling people who need little care and disenrolling the unprofitably ill. A relatively small number of very sick patients account for the vast majority of medical costs each year. A plan that dodges even a few of these high-needs patients wins, while a competing plan that welcomes all comers loses.”

“Upcoding, or making enrollees look sicker on paper than they really are to inflate risk-adjusted premiums. To counter cherry-picking, the CMS pays Medicare Advantage plans higher premiums for enrollees with more (and more serious) diagnoses. For instance, a Medicare Advantage plan can collect hundreds of dollars more each month from the government by labeling an enrollee’s temporary sadness as “major depression” or calling trivial knee pain “degenerative arthritis.” By applying serious-sounding diagnoses to minor illnesses, Medicare Advantage plans artificially inflate the premiums they collect from taxpayers by billions of dollars while adding little or nothing to their expenditures for care.”

“Lobbying to get excessive payments and thwart regulators. Congress has mandated that the CMS overpay Medicare Advantage plans by 2 percent (and even more where medical costs are lower than average). On top of that, Seema Verma, Trump’s CMS administrator, has taken steps that will increase premiums significantly and award unjustified “quality bonuses,” ignoring advice from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission that payments be trimmed because the government is already overpaying the private plans. And she has ordered changes to the CMS’s Medicare website to trumpet the benefits of Medicare Advantage enrollment.”

Insurance companies have always managed to adapt their schemes to whatever rules are adopted to minimize their adverse consequences. If we keep corporate insurers in place while we create a robust public option that covers people thoroughly, the people in the public option will disproportionally be people with high medical expenses. So a public option is really a subsidy to insurance companies, by making their profit margin higher since their population is healthier.

But insurance companies won’t be grateful and stop there. The high cost of the public option will create some combination of a high premiums, lower provider rates, or greater need for public subsidies. All of these things will make the public option look bad. And the insurance companies will start a smear campaign that the public option is bad because it's government insurance. They will say that only they can provide affordable insurance. The insurance companies will say the government is incapable of providing affordable insurance and that providers dislike public insurance because of their low payment rates. And since the insurance industry will still exist, they will still have lobbyists and they will be lobbying the government to make the public option more and more undesirable. In a climate like that, it would be impossible to create Medicare for all.

To put some numbers to the adverse selection process, recall that in general, 80% of healthcare expenditures are for 20% of the people. At best the administrative efficiency in a public option will be allow a it to be priced 10% lower than a comparable private plan that had the same population risk profile. If a private plan were able to discourage a few people who end up having high costs, so that their mix of those in the top 20% relative to the bottom 80% was 16/84 rather than 20/80, their estimated costs would be 15% lower. They could offer a comparable plan for a lower premium by betting that they would be able to market in such a way to are as to get this 16/84 mix, and if successful, could make excess profit. Their lower premiums would attract more of the 80% low cost clientele, leading to even more adverse selection. Corporate insurance companies are experts at targeted marketing, and it is hard to imagine that they would not be successful at this.